The Foreign Policy

Among many obstacles to the West’s effort to stop the carnage in Syria and alleviate the refugee crisis, probably the largest and the hardest to overcome is a colossal disjoint in the depth and breadth of commitment to the conflict between the United States and Russia.

There is little mystery as to the level of interest on the U.S. side. Despite what you might hear, for the Obama administration, Syria is but an annoying contingency, forced on the White House by circumstances, and with no consonance whatsoever with the president’s strategic agenda. For Vladimir Putin, it is an important part of a long-term ideological and geopolitical project, rooted in deeply held beliefs, a self-imposed personal mission, and domestic political imperatives of his regime’s survival.

The Russian president is not the easiest man to read. They have taught him well in the KGB Intelligence School and the Yuri Andropov Red Banner Institute (formerly the Foreign Intelligence Academy). But after 16 years of policymaking, there are at least two interrelated tenets in Putin’s credo we can be fairly certain of:

- The end of the Cold War was Russia’s equivalent of the Versailles Treaty for Germany — a source of endless humiliation and misery. The demise of the Soviet Union, in Putin’s words, was “the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the 20th century.”

- The overarching strategic agenda of any truly patriotic Russian leader (not an idiot or a traitor or both, as Putin almost certainly views Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin) is to recover and repossess the political, economic, and geostrategic assets lost by the Soviet state.

And so, not surprisingly, after his return to the Kremlin in 2012 after place-holding by his former aide Dmitry Medvedev, Putin turned sharply to the recovery of geopolitical assets, that is, the foreign policy part of the doctrine.

There was also a powerful domestic political imperative for this pivot to an activist foreign policy. Because of the country’s toxic investment climate, economic growth was slowing down even with oil prices at historic highs. Russian economists inside and outside the government warned that the Russian economy would no longer deliver the 8 to 10 percent growth in real incomes, as it had between 2000 and 2008, securing Putin’s astronomic popularity. In the words of Putin’s personal friend, former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Alexei Kudrin, the economy had hit an “institutional wall.”

Although Russia recorded the highest annual oil revenues in its history between 2010 and 2014, increases in the country’s gross domestic product grew progressively smaller, capital flight intensified, and investment came to a standstill. Public opinion polls consistently revealed people’s perception of the authorities at every level as deeply corrupt, callous, and incompetent. Most troubling for the regime, Putin’s popularity, which was and continues to be the foundation of the regime’s legitimacy, dropped by almost one-third between 2008 and 2011.

Kudrin called for a change of the country’s “economic model.” This is Putin’s nightmare: Gorbachev’s perestroika — an effort at economic liberalization — led to an uncontrollable political crisis and regime collapse.

Unwilling, therefore, to undertake liberalizing institutional reforms, Putin made probably the most fateful decision of his political career: He began to shift the foundation of his, and thus the regime’s, support and legitimacy from economic progress and the steady growth of incomes to what might be called patriotic mobilization.

The new policy rests on two interlocking propaganda meta-narratives.The new policy rests on two interlocking propaganda meta-narratives. One, that the West — first and foremost the United States — unhappy that Russia is rising from its knees, has declared war on Moscow in order to preserve their diktat in world affairs. Two, although threatened on all sides by implacable enemies, Russia has nothing to fear so long as Putin is at the helm: Not only will he protect the motherland, he will recover the Soviet Union’s status of being feared and therefore respected again. On national television, where an overwhelming majority of Russians get their news, foreign policy has become a mesmerizing kaleidoscope of breathtaking initiatives and brilliant successes.

There followed the annexation of Crimea and the hybrid war in Ukraine.

A patriotic fervor at the sight of the motherland besieged yet somehow victorious, mightily shaping world events while acting as a moral and strategic counterweight to the United States, has obscured for millions of Russians the increasingly bleak economic reality and repression of dissent. As the great Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov put it in the poem “Ismail-Bey,” “Yes, I am a slave but I am a slave of the master of the Universe!”

Putin has saddled the tiger of patriotic fervor and made it trot at his command. The problem with this mode of transportation is that the tiger requires more meat, and the bloodier the better.

Thus when the war in Ukraine began to lose much of its propaganda flesh, Putin turned to Syria. On Oct. 20, 2015, in the Kremlin and on national television, Putin shook hands with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad — and overnight Syria replaced Ukraine as Russia’s main battlefield. Assad, as a New York Times reporter in Moscow put it, was “lionized” on Russian television. The survival of the old Soviet Union’s client, under deadly fire from the pro-democracy opposition and the Islamic State, became a domestic political imperative.

Given these stakes, it is no surprise that Russia’s presence in Syria is open-ended — and allocated as many resources as necessary to accomplish its objectives.

Hence, Russia’s so-called withdrawal from Syria amounted to little more than maintenance rotation and operational adjustment. In the words of the former head of the Russian Air Force, Gen. Vladimir Mikhailov, “We are not withdrawing all our forces [from Syria] but only the ones we don’t particularly need for the present state of the operation.” And such personnel and military hardware that has been taken out, could, as Putin put it, be returned “in a matter of hours.” Russia continues to provide Assad’s army with close air support and precision strikes, including with Iskander tactical missiles, artillery support, intelligence, and targeting.

It is in this context that we must view the utter futility of President Barack Obama’s calls to Putin and Secretary of State John Kerry’s trips to Moscow in search of “common ground.” It’s worse than useless. Played ad nauseam on Russian state television, every such call, every clink of champagne glasses with Obama at the U.N. General Assembly, every visit by Kerry, boosts the regime’s domestic legitimacy. If the leaders of the United States — which is ultimately the only nation that counts to Russians (just as it was in the Soviet days) — call you, come to see you, beg you, then surely it reaffirms that you are the most important nation in the world. “It does not matter what they [Putin and Obama] talked about nor what was the result,” wrote a leading independent Russian political analyst. “More important is that they themselves call ours Putin.

The media have feasted on Kerry thanking Putin for the “privilege” of being in his, that is Putin’s, presence, as he did at the news conference after his trip to the president’s Black Sea residence in Sochi last year. Russian TV replays Putin slapping Kerry on the shoulder and addressing the U.S. secretary of state as “ty” — which is the informal “you,” used to address close friends — but also children and subordinates.

And then there is the bizarre charade of the Ceasefire Task Force of the International Syria Support Group. Meeting most recently in Vienna, this august gathering of foreign ministers tied itself in knots over the strikes by Assad’s planes on Syrian cities and the inability to deliver humanitarian aid. All the while, sitting next to Kerry was the group’s co-chair, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, whose president could stop the carnage with a 30-second phone call to Assad. Instead, Russian planes, along with Syrian bombers — supplied, maintained, and targeted by Russian forces — are reducing Syria’s largest city, Aleppo, to Stalingrad-like rubble, just as Putin did to Chechnya’s capital, Grozny, in 1999-2000.

In Syria, the West wants peace. But Putin needs victory. And so it will look like this: The secular, pro-Western opposition will be either decimated or forced to disarm as part of a U.S.-Russian “peace process.” The West will be confronted with the repugnant choice between Assad and a combination of the Islamic State and the Nusra Front, an al Qaeda affiliate. And so Assad’s regime will survive. Meanwhile, Russia will be restored to the Soviet Union’s position as an indispensable international player and key actor in the Middle East.

Make no mistake, Putin will stay and fight until these goals are achieved — unless the costs of the campaign exceed it benefits.Make no mistake, Putin will stay and fight until these goals are achieved — unless the costs of the campaign exceed it benefits. And right now, that’s extremely unlikely given the Obama administration’s views on the Russian involvement. As Kerry put it at the end of March, “I see no threat whatsoever to the fact that Russia has some additional foundation in a Syria, where we don’t want a base, where we are not looking for some kind of a long-term presence.” For Putin, the war in Syria is low-risk, high-reward — and there is little chance that Washington has any ability or desire to tip the scales in the other direction. And Europe already seems to be agonizing about the sanctions imposed in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the proxy war on Ukraine.

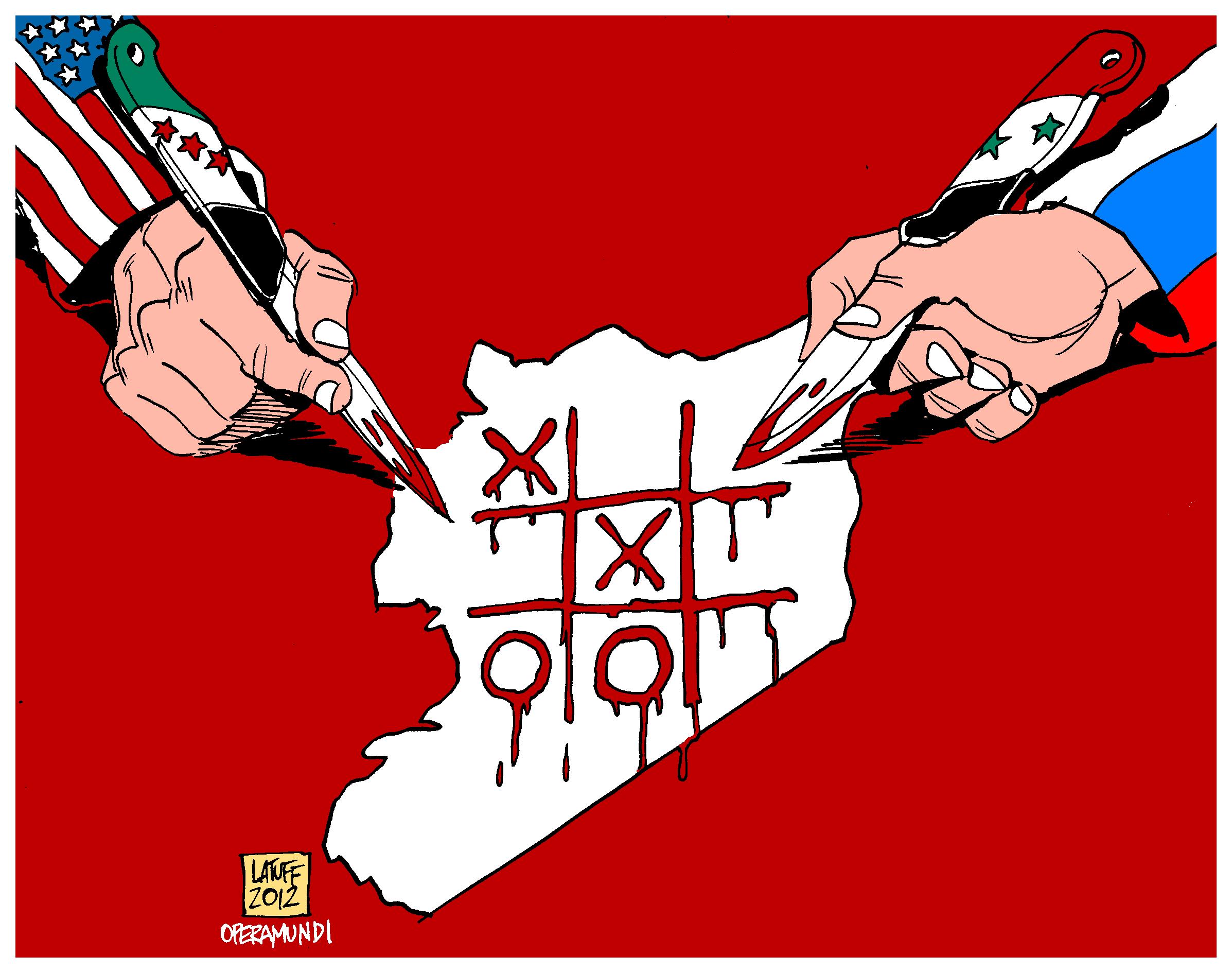

Russia is playing chess in Syria. To say that the United States is playing checkers would be to grossly overestimate the intellectual, moral, and military commitment. Tic-tac-toe is about right.