The New Yorker

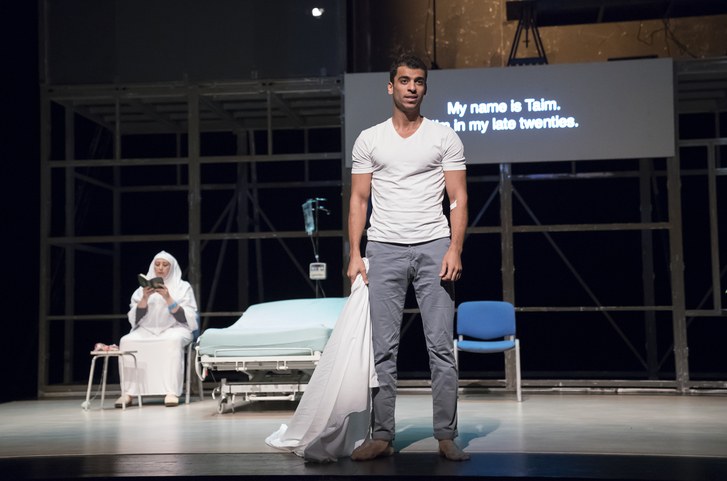

When one’s entire life is spent waiting, how does one measure the time? In the play “While I Was Waiting,” which on Saturday wrapped up a run as part of the Lincoln Center Festival, Omar (Mustafa Kur), a former telecom worker from the less affluent and besieged Damascus suburbs, gives us the sum of his life in days—10,749 to be precise. We quickly learn, however, that these only account for twenty-nine of his thirty-one years, as he has spent the past two years no longer alive but not quite dead, suspended in a state of unconsciousness after the pummelling he received in Syrian prisons. Omar’s body, we assume, remains in the darkness of some cell, but we meet him as he hovers on a scaffold overlooking the stage, keeping him near but apart from the characters who live fully in the corporeal world. Joining him on that liminal plane is Taim (Mohammad Alrefai), the play’s protagonist. He lies in a coma, having suffered his own beating by government thugs, at a checkpoint in Damascus, while at work on a film about his family and the 2011 uprising against the regime of Bashar al Assad. Taim’s mother, sister, lover, and best friend are constant visitors in his hospital room. Onstage, these actors interact with his empty bed as Taim and Omar speak to us from above.

The men, in their in-between state, are, of course, a metaphor for Syria, which is also neither dead nor alive, paralyzed by war but surviving in what the play’s director, Omar Abusaada, has called the “grey zone.” In the past several years, the country has become a theatre where absurdity comes to plant its flag, where the cruel, the unforgivable, and the unfathomable surpass each other by the hour. For many Syrians, as for Taim, living through the past six years has been an out-of-body experience, like viewing a film of someone else’s life. Unable to return to how things were before and uncertain of what comes next, the people of Syria are in waiting—for peace, death, escape, exile, or return.

In “While I Was Waiting,” an entirely Syrian cast and crew bring this reality to a New York stage, capturing dynamics rarely explored by non-Syrians, who tend to conceive of the country’s predicament as simply a “war story.” Abusaada, the director, is still, remarkably, based in Damascus, while the playwright, Mohammed Al Attar, has been given asylum in Germany. The rest of the team is scattered across the Middle East and Europe; most of their families are still inside Syria. (Banned at home, the play had its first run at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts, in Brussels.)

As the story unfolds, we learn that, when Taim was still a child, a scandal ruined the lives of his family (though that is now relative—the damage of a loss of honor is nothing compared to the ruin now meted out daily). Shortly after his parents’ twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, Taim’s father, a corrupt engineer, was found murdered with his mistress, most likely at the hands of his criminal associates. In response, Taim’s mother turned to religion. She donned the veil and forced it on his sister as well, embodying the role of the victimized and pious widow, and refused to admit she had any idea about her late husband’s double life. Her daughter, who has since removed the veil and moved to Beirut, to escape her family’s silence and shame, damns her mother, Taim, and herself, as well, saying bitterly, “We knew and we stayed quiet. We buried our heads in the sand.”

The comment could apply equally to all of us Syrians. “While I Was Waiting” forces us to remember the country’s Taims and Omars—since 2011, tens of thousands of Syrians have disappeared or remain unaccounted for—but it is also an indictment of the living. Yes, people living under authoritarian regimes are the victims of those who rule them; they also, however, become bystanders to brutality. In Syria, we are complicit even if not directly to blame.

I came to understand this when I left New York City for Damascus, in April of 2011, to restore my grandmother’s house and work on a book about her. (Her experience in her final years was eerily to similar to Taim’s.) I voraciously consumed tomes on other unjust regimes, from North Korea to East Germany to apartheid-era South Africa. It was then that I read the words of the South African poet Breyten Breytenbach and felt revealed, exposed: “The two of you, violator and victim (collaborator! violin!) are linked, forever perhaps, by the obscenity of what has been revealed to you, by the sad knowledge of what people are capable of. We are all guilty.” On some level, we Syrians are aware of this and, whether consciously or not, we feel deep shame.

The Assad regime, père through fils, has elicited our collusion through several insidious strategies, one of which is placing a constellation of security offices to carry out the regime’s surveillance of its people right in the middle of regular city neighborhoods, close to where we live, shop, and eat. Known collectively as the mukhabarat, many of the offices have underground torture chambers, from which countless Syrians have never emerged. Some of the Damascus locations invoked in “While I Was Waiting” are familiar in part because of the prisons or dreaded mukhabarat branches located in their midst.

Prior to 2011, Syrians made all kinds of compromises just to stay in the country or to be allowed to return, on visits, to its embrace. Such bargains were not impossible to understand—home is home. Since then, though, nearly six million Syrians have fled the country, and many of them—whether in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, or Europe—now find themselves facing a new kind of interminable wait. At the end of the play, the still comatose Taim is released from the hospital and brought home, and his family continues to wait—optimistically—for the day he will wake. His lover, though, has decided to try her chances in Turkey, and the rest have gathered to see her off. In it, he narrates how he spent the entire day walking Damascus, and he confesses that he, like so many others, is finally considering taking to the sea toward Europe—a rejection of the regime and the jihadists alike. Now, in the film clip, which is reënacted by Taim onstage, he is on his roof late at night, in quiet reverie, watching the city that he loves, serene after a rainfall. Though Taim has work he must finish and preparations to begin if he is to leave, he lingers to smoke a last cigarette. He tells work, travel, everything else to wait, just to buy a little more time with the beautiful and ancient place he calls home.