The Wall Street Journal

When Syrian forces launched a chemical attack on the town of Khan Sheikhoun two months ago, no one was watching more closely than Israel’s military elite. Of all the existential threats their country fears, chemical weapons rank high on the list. In 1967 Israeli fear of a chemical attack helped spark the Six Day War, the most transformative conflict in the modern history of the Middle East. Continued use of chemical weapons in Syria poses a similar threat to Israeli security—and may foreshadow another regional war.

The first country to use chemical weapons in the Middle East was Egypt. During the 1960s, President Gamal Abdel Nasser deployed poison-gas bombs during the North Yemen Civil War. Unknown to the Egyptians, Israel had obtained a front-row seat to study their military capabilities.

The conflict involved the Yemen Arab Republic, founded in 1962 after a coup d’état deposed the country’s religious monarch, Imam Muhammad al-Badr. Egypt took the republican side, sending mechanized and heavily armed battalions to aid the revolutionaries.

The monarchist northern tribal militias, aided by a cadre of British and French mercenaries, took shelter in the country’s mountainous highlands. The problem was finding a way to resupply their position. After concluding that an air resupply was vital, the mercenaries began searching for an ally willing to orchestrate airlifts into hostile and unfamiliar territory. In the end they turned to Israel, the only country with something substantial to gain from an extended guerrilla war against Egypt.

Between 1964 and 1966, the Israeli Air Force flew 14 missions to Yemen, airlifting vital weapons and supplies to beleaguered tribal outposts. Although the identity of the supplier was a closely guarded secret, these airlifts constituted an important physical and psychological lift for the tribal militias.

In exchange, Israel received well-informed intelligence from its own pilots and British mercenaries on the ground. The Israelis’ main contact was Neil McLean, a former Special Air Service soldier and member of the British Parliament. McLean passed to Israel details of Egypt’s military activity, even samples of its chemical weapons.

The Egyptian Air Force had been dropping the poison-gas bombs, targeting militias hiding in a network of caves, with increasing frequency and precision. This news alarmed Israelis, many of whom had lost family and friends to Hitler’s poison-gas chambers only two decades earlier. They were haunted by the prospect of a similar fate befalling them in a gas attack on Tel Aviv or another Israeli city. A sense of looming existential threat pervaded Israeli society, down to the local school district. In one emergency meeting in May 1967, teachers debated security protocols. In the event of an air-raid siren, should students be ushered into the basement bunkers? Or would climbing to the rooftops be better for escaping poison gas?

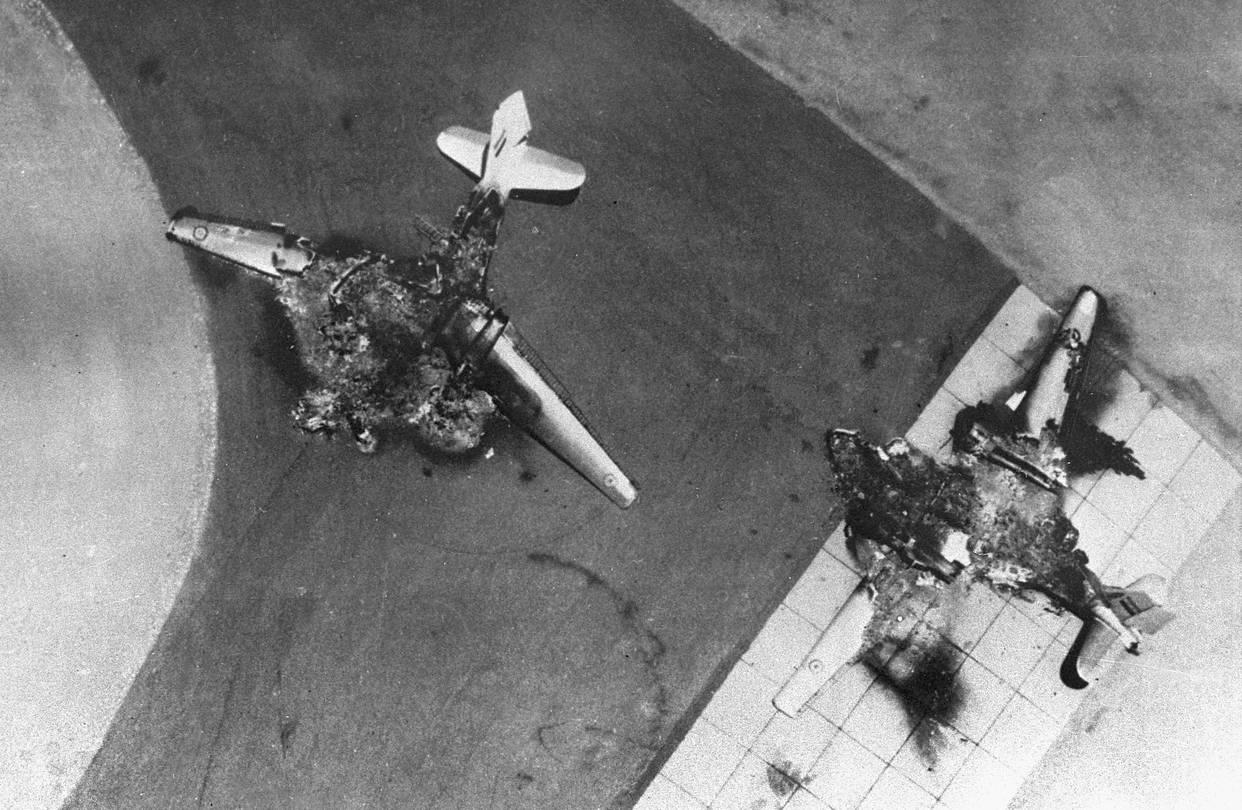

The fear of a chemical attack undoubtedly factored into Israel’s decision to attack Egypt’s air force pre-emptively on June 5, 1967. Over five hours Israel destroyed 300 Egyptian planes and disabled 18 airfields, eliminating the short-term threat of chemical warfare. But the long-term danger has remained.

There is a clear parallel to the current conflict in Syria. What made the 1960s crisis in Yemen so dangerous was that the international community did not respond to Egypt’s use of chemical weapons. The Yemeni civil war was waved off as merely an intra-Arab conflict. Without visible international assurances that chemical warfare would not be tolerated, Israel in 1967 felt compelled to eliminate the threat before it arrived.

In the barrage of Tomahawk missiles President Trump launched against Syria in April, the U.S. provided some response to the latest chemical attack. Failure to follow up this show of force with collective international action—making clear to Israel that further chemical warfare is off the table—may push the Middle East toward another destructive regional war.